Advertisement

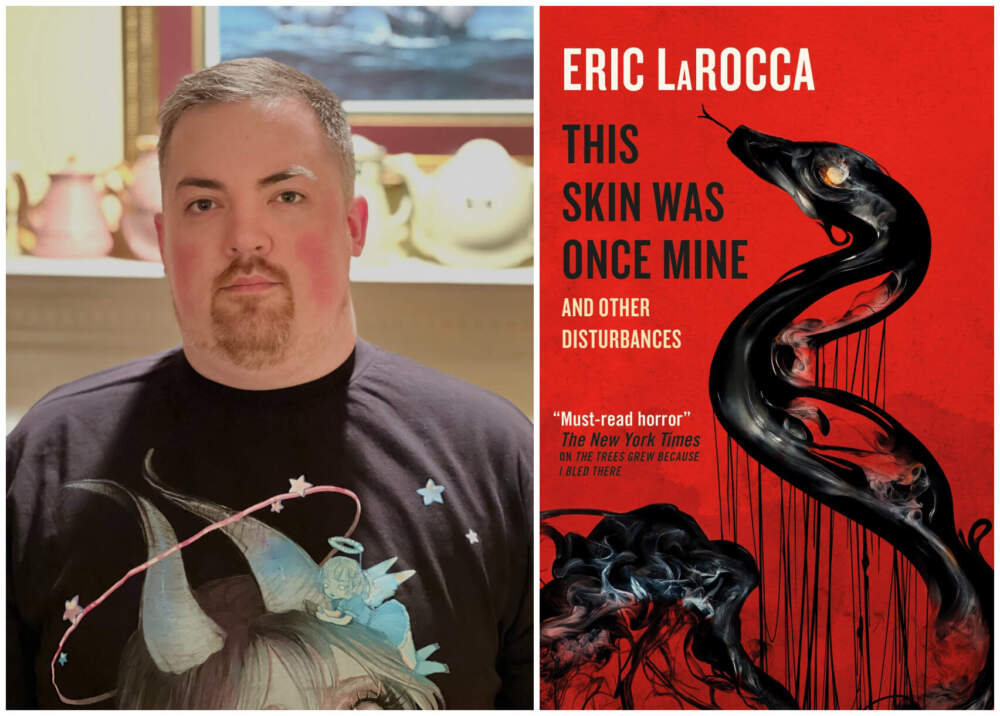

For author Eric LaRocca, horror is a form of healing

You can try reading “This Skin Was Once Mine and Other Disturbances” in the daylight. But even sunshine won’t be able to banish the deep-body chills and that pit-in-your stomach creepiness summoned by the four thematically linked stories in the volume.

Sure there’s blood and brutality. Brushes with Lovecraftian cosmic horror. Physical pain portrayed as a thrilling new joy for characters, who seem to opt in to troves of trauma. But, as LaRocca puts it, “There is a through line in the stories of the cruelty of humanity. How we hurt each other. How we hurt the ones that we love the most.”

In other words, the kinds of fears that can fester even in the day. And at the end of a surprisingly buoyant conversation given the stories’ subject matter, LaRocca (who uses both he and they pronouns) has a lightbulb moment. “I'm kind of realizing the whole collection is just, like super, super gay,” they add with a laugh.

“This Skin Was Once Mine and Other Disturbances” is the latest release from LaRocca, who pens short stories, novellas, and novels, and whose chilling work The New York Times has dubbed “must-read horror.” Though the author is well-established in the genre — their 2021 novella “Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke” went viral on TikTok, earning a Splatterpunk Award and they’ve also been twice nominated for a coveted Bram Stoker Award — this latest release marks a significant first. It’s the first of their work to feature a content warning at the jump, at the behest of Titan, the book’s publisher.

“A lot of people have already said, like, ‘If you're reading a book by Eric LaRocca, that in and of itself is a trigger warning,’” LaRocca says. “But for this book, it felt like [a content warning] was very necessary. And I was totally on board with that.”

But if you steel your stomach and read on, like a group of teenagers in a horror movie breezing by the KEEP OUT signs in front of an abandoned house, the resulting stories are gifts wrapped in gore. The title story, a tale of generational trauma called “This Skin Was Once Mine,” sees the main character returning to her family home and confronting her childhood abuse following the death of her father. In “Seedling,” the main character reels from grotesque discoveries as he comforts his father following the death of his mother. “All the Parts of You That Won’t Easily Burn” describes a man on a mission to buy the perfect knife for his husband ahead of a lavish dinner party. And in the chair-kicking closer, “Prickle,” two friends reunite after a long absence and terrorize strangers as part of a twisted game. After meticulous setups — LaRocca winding razorblade-tipped clock gears — the same formula holds true for each story: awful things happen to everyone.

Horror is the most cathartic genre because you experience the trauma, you experience the pain with these characters and you come out on the other side.

Eric LaRocca

Each of these stories is a gothic cathedral — ornate and rendered with a beauty that’s as much about shadows and dark alcoves as soaring heights. “I begin to watch a small black velvet-bodied spider sew a web along the rim of an empty, sun-bleached birdbath,” the main character observes in “This Skin…” In “All the Parts…,” the main character notices that “The shopkeeper seems to study him with the inquisitive eyes of a sculptor — meticulously calculating his design, his masterpiece, his creation.” And except for the brief mention of a cellphone in “Seedling,” LaRocca relishes in shaping settings suspended in time. Stories might take place ten or a hundred years ago. Or foggy alternate presents, that seem suffused with an ambient queerness, even if the characters aren’t labeled as such.

“Especially queer people, the world just wants to, like, annihilate us and we implode a lot of the time under this pressure,” LaRocca says. “And I'm really interested in writing about those complex queer narratives where things aren't OK. Things are difficult and arduous and really grotesque.”

“Difficult” is an understatement, as their characters are living through their most awful moments, rather than reflecting back on or learning from the trauma. And LaRocca isn’t alone in linking queer narratives to horror. The genre has explored queer narratives and has summoned queer fans for decades, from the queer-coded villains in silent flicks, to the worship of camp queen Elvira who debuted in the ‘80s, to 2009’s seminal Sapphic horror “Jennifer’s Body,” and the recent Netflix series “The Fall of the House of Usher,” which features a ton of queer representation.

“We are perceived as the ‘other’ by a lot of society, and we find solace in identifying with the other in the story,” as LaRocca puts it. That “other” is often the monster or the outsider in the horror story — just take a look at “Carrie.” There’s power in writing about the horrors of humanity, “like an exorcism on the page.” Something personal, too, as LaRocca admits, “I'm terrified of pretty much everything, but for me [horror] is a way to reclaim power. A power to terrify other people before they have a chance to inflict anything on me, you know?”

LaRocca doesn’t limit those razor-sharp observations to just themself. Characters in the stories wield words like weapons, delivering brutal judgments on relationships. But don’t let that lull you into a false sense that these tales lean more psychological than horror. Rather, the physical frights are rendered with explicit, glistening gore and set against claustrophobic backdrops. Tempting at points, if the collection was a movie, to tear your eyes from the screen.

But why do so many keep their eyes glued? Call LaRocca’s tales, and the fascination with horror in general, exposure therapy. “Horror is the most cathartic genre because you experience the trauma, you experience the pain with these characters and you come out on the other side,” they add. “All trauma leads to transformation.”