Advertisement

A once-enslaved man’s music was hidden for centuries. Go on a journey to rediscover his melodies

A few years ago, when Americans nationwide began on a path of racial reckoning, parishioners at a small Connecticut church started to explore their community’s past — and discovered historical ties to slavery.

Volunteers from St. John’s Episcopal Church in Essex searched through old archives. They eventually discovered a 1777 probate record.

It listed an enslaved boy named Sawn or Sawney.

Then came another clue: a 1790 newspaper ad from a local farmer, offering a reward for the return of an enslaved musician who’d run away.

“Sawney is a fiddler,” the ad reads. “And he took with him the fiddle.”

The find would send volunteers on a meticulous search to learn more about Sawney and to reconstruct his story. They learned his full name: Sawney Freeman. And the group would eventually learn he wasn’t just a violinist, but a composer. They would find handwritten copies of his music tucked away in a Connecticut library’s archive, and painstakingly prepare it for contemporary musicians.

“I was astounded that it even survived,” says Jim Myslik, one of the St. John’s church volunteers. “The probability of something that's really ephemeral like that surviving 220 years is really vanishingly small.”

And now, for the first time in centuries, Sawney Freeman’s melodies are being performed.

“I think we're really privileged to hear his voice across over 200 years,” Myslik says. “It’s really moving.”

‘He took with him the fiddle’

For centuries, most people didn’t know about Sawney Freeman or his music.

It’s not surprising. This history wasn't taught in school, but slavery has deep roots in Connecticut and across New England. Thousands of people were enslaved in the state. Dating back to before the Revolutionary War, the state profited off the work of enslaved people both at home and abroad.

Historians have long documented the so-called “Triangle Trade,” and enslaved people in Connecticut left narratives describing it, too.

“Almost all the lifeblood and cash to run this community came from slave labor,” Myslik says.

“While there might only have been a handful of slaves [in this area] … in 1800, the whole economy of this area was based on trade with the West Indies."

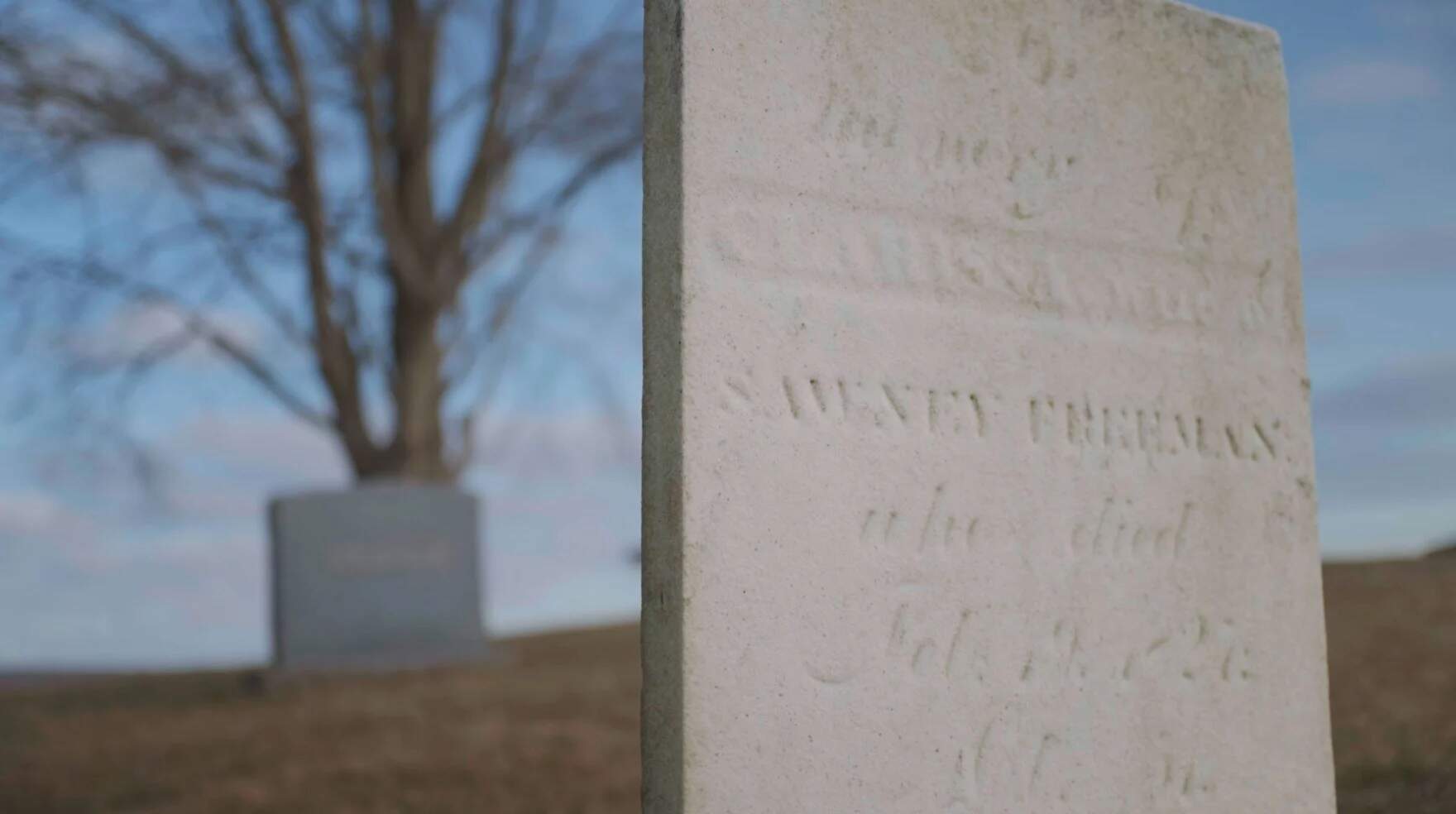

Researchers believe Sawney, who died in the late 1820s, was born into slavery in the home of Samuel Selden, a major landowner in Lyme, Connecticut. Church volunteers teamed up with a local historical society and the Witness Stones Project, a group that works with communities to restore the history and honor the humanity of the enslaved, to learn more about Sawney’s life.

During the Revolutionary War, they found Selden was a colonel. But, in 1776, he was imprisoned in New York, where he died.

Col. Selden's son would emancipate Sawney in 1793, records show.

“This is like detective work, right?” Myslik says. “He probably was mostly an agricultural worker but he also worked in shipyards.”

But that 1790 runaway ad also clued Myslik and the group into another part of Sawney’s life – his work as a musician.

There were other clues, too.

The 1864 book “History of Durham, Connecticut” by William Chauncey Fowler describes hearing violinist Sawney Freeman perform in the town.

“He accompanied his violin with a sort of organ, which he played with his foot … It added greatly to the volume of the music,” the passage reads. “At this ball besides contra dances they had jigs and reels.”

‘An instrument of liberation’

Historians find a surprising number of runaway notices for enslaved musicians, particularly fiddlers. Violin was a go-to instrument at social gatherings at the time – not just for enslavers, but also the enslaved.

The documentary film “Black Fiddlers” explores this history.

Music could be a vehicle of resistance in early America, says filmmaker Eduardo Montes-Bradley.

“We need to look at the fiddle, the violin, as an instrument of liberation in a sense, and freedom,” Montes-Bradley says.

Enslaved musicians were able to access better-quality work. They were hired out to play at parties and weddings. At the same time, the violin offered hope to enslaved musicians planning an escape.

“There are several challenges if you decide to run away,” Montes-Bradley says. “One is: Would you make it? And then: How are you going to survive if you make it? A fiddle or a violin is very easy to conceal … it’s easier to conceal than a piano.”

Another ad, another clue

The volunteers from St. John’s church would soon discover something more.

Sawney was not only a fiddler. He was also a composer.

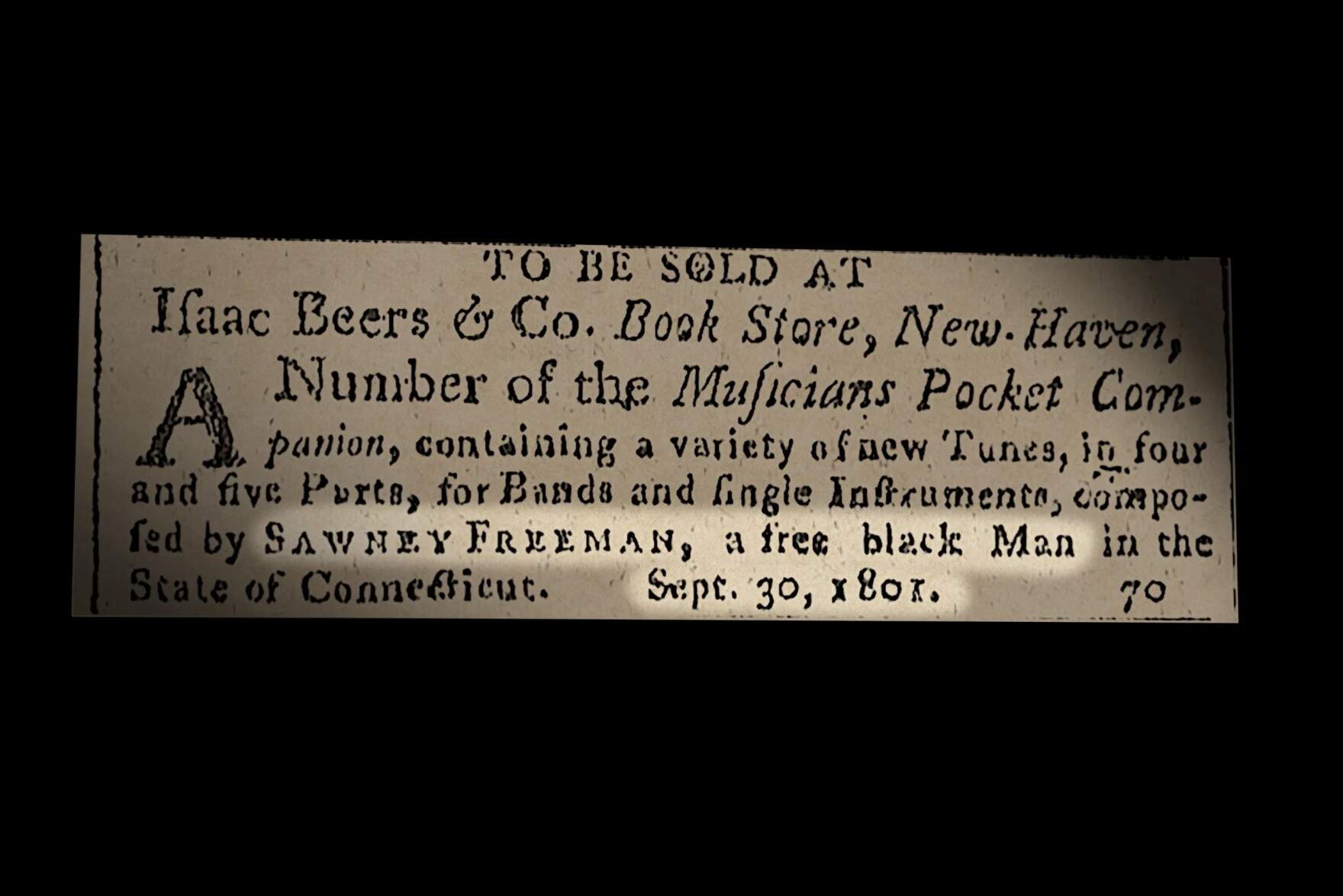

“In 1801, there was an ad in the Connecticut Journal in New Haven that advertised something called the ‘Musician’s Pocket Companion’ written by Sawney Freeman, a free man of color from Connecticut,” Myslik says.

“Exceptionally unusual for the time.”

In fact, it’s evidence that Sawney is one of the earliest published Black composers in the United States.

Intrigued, the church group found an online database of American music collections. It listed a manuscript of music attributed to Sawney Freeman as part of a library collection, stored in an archive only about 40 miles away.

‘The paper is quite fragile’

Deep in the archive at the Watkinson Library on the campus of Trinity College in Hartford, Eric Johnson-DeBaufre walks through rows of library stacks standing in chilly air.

“Paper likes that,” he says.

The librarian digs into a rare and special collection where the Sawney Freeman music manuscripts are kept.

With care, he lays the old paper out on a table.

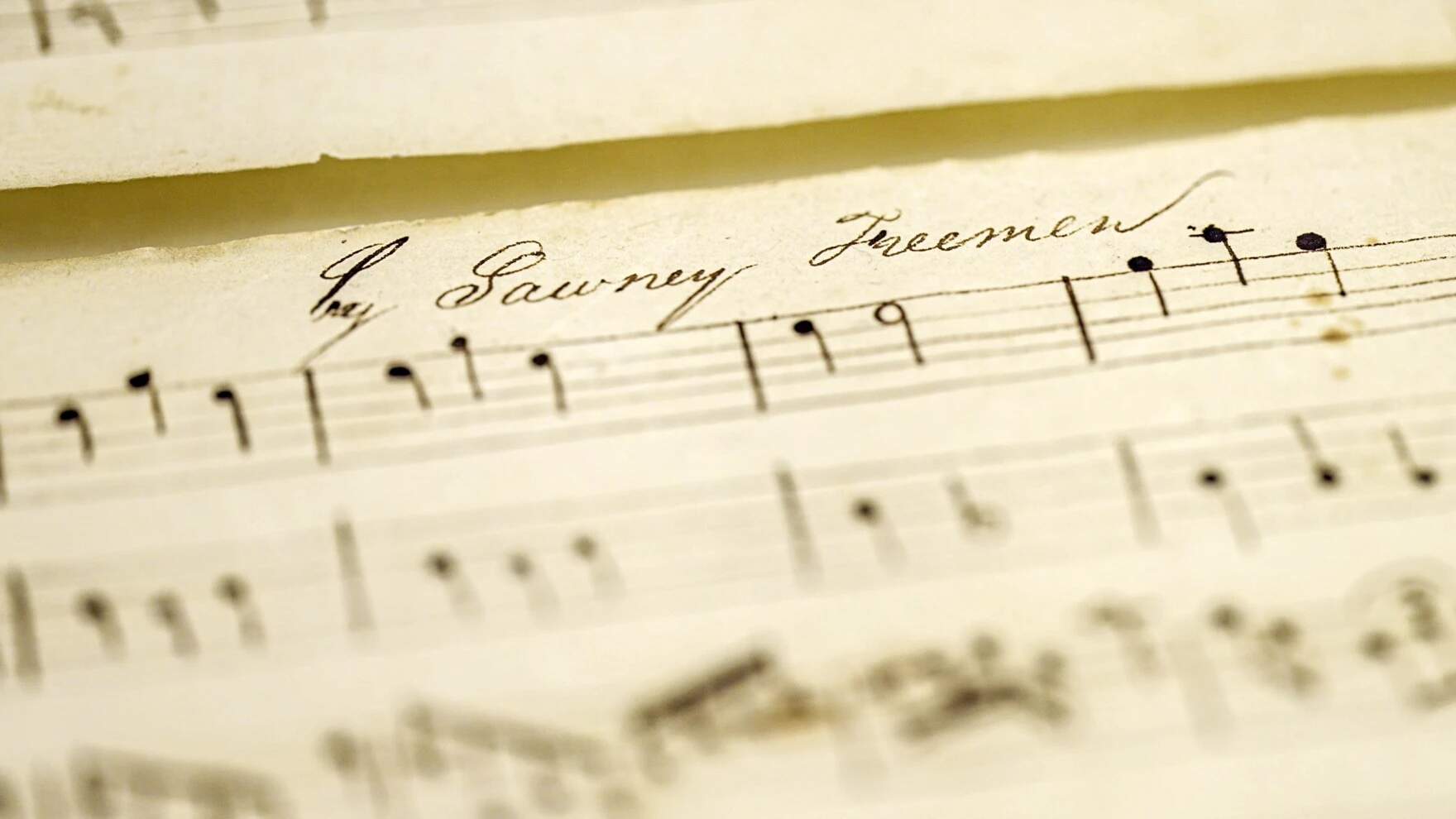

“The paper, as you can see, is quite fragile-looking,” he says. “It is all done by hand in a very clear, I think, dark ink. You have the names of tunes up at the top and then the composer to the side.”

Near many tunes are the words “By Sawney Freeman” or “by S.F.”

The manuscript is from 1817. It’s handwritten with music for solo violin as well as ensembles of five or six instruments.

It includes a blend of musical styles, some leaning toward Western European classical music. Other tunes have more of a folk-style fiddle feel.

Popular songs of the day, like “Polly Put the Kettle On” and “Yankee Doodle,” are scattered in between.

So how did this manuscript, which is over 200 years old, wind up in this library in Hartford?

It once belonged to the father of the Watkinson Library’s first librarian, Johnson-DeBaufre says.

“I think it’s probably for that reason that this is in our collection,” he says. “It makes me wonder: How did he know about Sawney Freeman? Because this copy book seems to be the only record of Sawney Freeman’s musical compositions that has survived.”

The manuscript was part of the collection of Gurdon Trumbull, a merchant from Stonington, Connecticut, whose family took an interest in abolition. Family members had collected a variety of material regarding local Black residents.

“It's clear that the family had some deep sort of sympathies with the plight of enslaved Black people in the country,” Johnson-DeBaufre says.

‘This is revolutionary’

Music is central to worship at St. John’s in Essex, and members wanted to include Sawney Freeman’s work as part of their services.

Once the manuscripts were rediscovered, the library digitized the fragile documents and the church music director transcribed the notation into something contemporary players could read.

In February, St. John’s gathered together musicians for a first-ever recording of works by Sawney Freeman.

The recording took place in an elegant library at the historic Waveny House in New Canaan, Connecticut.

Among the three violinists, one cellist and a piccolo and flute player, the excitement is palpable. The group performed pieces named “St. Alban's,” “Liberty March,” “Solemnity,” and “The New Death March.”

There were upbeat dance tunes and quieter, reflective pieces. The handwritten melodies of Freeman suggest he'd likely improvise during long nights performing for dance engagements in Connecticut. Musicians at the 2024 recording session honored the composer by riffing on a few of his tunes.

Jessica Valiente, who played the piccolo and flute, says Freeman’s music was not what she expected.

“I didn't expect it to sound quite so ‘colonial,’” Valiente says. “I know a little bit about Black fiddling traditions and I expected it to be more like fiddle tunes and a few of them were. But some of them seem to be from a church tradition or from more of a martial tradition.”

For the musicians, performing this newly-discovered music was moving and poignant

Violinist Ilmar Gavilán, a member of the Grammy-winning Harlem Quartet, says the experience was enlightening and heartening.

“As a Black violinist myself, I was very surprised because I always thought this was a later event of people of color playing European instruments,” he says.

The music can be a lesson for today’s musicians of color, he says.

“It also informs the younger generations of specifically Black string players that this legacy existed way before we even imagined. You just think, ‘Oh my gosh, that really did exist. I’m not alone! Somebody else was in love with the violin!’”

Briana Almonte, a 19-year-old violinist, says the experience of playing Sawney Freeman’s music was thrilling.

“An early Black composer, composing these works. I feel like this is revolutionary,” Almonte says.

It’s important that young people learn about the contributions of early Black artists, Valiente says.

“I think that when people imagine the past, they often imagine a past where we weren’t there or we were just sort of doing the drudgery work,” she says. “We made many contributions that people have yet to know.”

Sawney Freeman’s contributions are still being uncovered. And now, after centuries of silence, his musical voice sings once again.

“It’s important to play this music,” Valiente says, “because people need to know that we were here.”

Listen to Sawney Freeman's music:

This story is a production of the New England News Collaborative. It was originally published by Connecticut Public as part of their 'Unforgotten' series chronicling Connecticut's ties to slavery.