Advertisement

This Boston guitar pedal builder is shaping the sound of rock music

The guitar in John Snyder’s lap is wired through a nondescript aluminum box covered in an array of knobs and switches. As Snyder manipulates them, the tone coming from his amp warbles in otherworldly ways. One minute it sounds as if it’s coming from the far end of a cathedral made of metal, sharp and resonant but also beautiful. The next, a low growl that almost sounds human fills Snyder’s sunlit Waltham workshop.

That little box he’s messing with is a prototype Snyder is perfecting for his guitar pedal company, Electronic Audio Experiments (EAE). He’s reticent to share too much about it. “You’ve got to kind of keep people on hooks with the new stuff,” he says, grinning.

EAE has been able to carve out quite a niche in the guitar pedal industry, a world where artistry meets electronics. Thousands wait for the newest product online, and the company has shaped the sound of influential Boston bands Pile and Kal Marks, and bands further afield like Los Angeles-based post-hardcore rockers Touché Amoré.

Its footprint is outsized for a company of four, which was operating out of a “definitely illegal” basement apartment in Brighton just nine years ago. “We’re in a perpetual state of backorder,” Snyder admits.

A longtime guitarist with a doctorate from Boston University in electrical engineering, Snyder started building pedals in 2015 to solve a problem for the band he played in. None of the distortion-creating units he could find gave him enough control. So, he took a stab at making his own. The result of his efforts wasn’t pretty. The exposed circuit board was crowded by a mess of wires, but it formed the electronic basis for the Longsword, the pedal that launched EAE.

“I realized there were others out there looking for the same sound I was,” Snyder says. “It was just luck.”

Pedals are an integral part of a guitarist’s arsenal. Using their feet to trigger an array of interconnected circuit boxes, musicians can harness the forces of distortion, gain, reverb and delay, dialing in a sound that’s specific to them.

“They’re like spices,” explains Pile frontman Rick Maguire. “You have salt and pepper,” typical units that distort or add echo. “And then there are some like turmeric, the more experimental ones.” Like the one Maguire recently built with Snyder called Mirror House, a device that detunes a guitar tone into an ethereal warble. “You don’t need a lot of it, it goes a long way.”

There are endless options available to a budding guitarist ranging from a $30 mass-produced Behringer to hand-crafted boxes that go for tens of thousands of dollars. It’s an incredibly competitive space, but Snyder has been able to distinguish himself through a close partnership with, and understanding of, musicians.

Touché Amoré guitarists Clayton Stevens and Nick Steinhardt came to Snyder in 2019, “chasing a sound” as Stevens puts it, for the band's latest album, “Lament.”

Snyder describes Limelight, the pedal he built with the band that was released in 2020, as “a chimera of classic circuits.” It’s a perfect distillation of Snyder’s abstract vision to help musicians “sound more like themselves.”

Watching the process was gratifying for Stevens. “You can talk to [John] about the feeling of something, like a musician would, and he can somehow translate that electronically,” he says. “That’s what makes him really good at what he does.”

2020 was a defining year for Snyder. Having completed his doctorate, he was on the job search, turning down offers for positions in the defense industry. “Something cool will come up eventually,” he hoped. “But it didn’t because the economy was doing weird stuff.”

Throughout school, selling pedals like the Longsword and another called the Halberd was just a side hustle for a broke grad student. For a while, manufacturing consisted of getting a few friends together around a tarp-covered folding table, ordering a pizza, and soldering and assembling through the night.

Demand for pedals was exploding with so many people turning toward indoor hobbies as a result of the pandemic, and Limelight was a huge success. Snyder, struggling to fill orders, realized, “This is a full-time job, this is how I make my living.”

There were the typical challenges that come with launching a business. “For two years, it was like, ‘What is this form? What kind of account do I open?’” Snyder recalls. “It was a trial by fire.”

Snyder and the small team he hired were also at the whim of Boston’s highly competitive real estate market. Just over a year after moving into their first workshop at 119 Braintree St. in Allston, they were forced to relocate when the owner of the building decided to redevelop it into office, lab and retail space.

It was a painful moment that left Snyder disillusioned with the city he spent the last two decades in. “There is a cultural problem here where art of a certain kind just doesn’t have a place,” he says.

But Snyder has lived in New England all his life. He couldn’t imagine doing business elsewhere. So when analog synth distributor synthCube offered EAE a space in its Waltham warehouse, Snyder was happy to accept. Still, he seems anxious about the future. “How long is the space going to last?” He asks himself. “There is an impermanence to everything.”

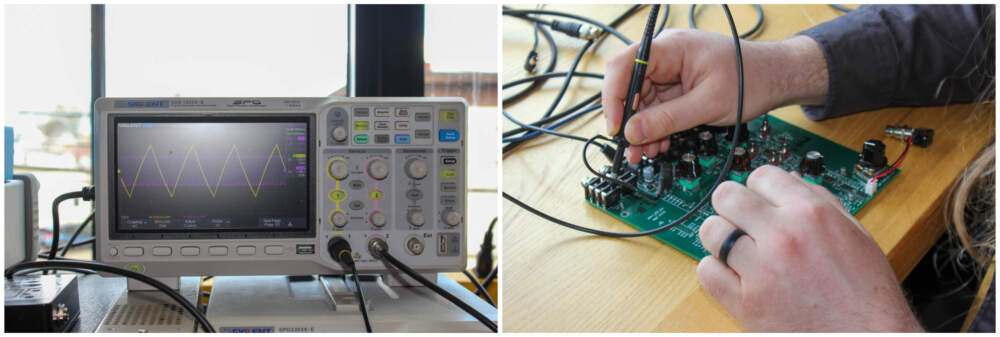

Located in a corner of the second floor, the EAE workshop is crammed with amplifiers, circuit boards, soldering irons, audio analyzing tools and the kind of baking racks you’d expect to find in a kitchen. “The trays are actually very good for storing pedals,” Snyder says. Pulling one out, he reveals an array of Longswords ready to be served.

With his doctorate, Snyder seems overqualified for an industry largely made up of untrained musicians and artists. Pedal circuits haven’t moved far from where they began in the 1960s, and Snyder’s Boston University lab work involved integrated photonics, a field at the intersection of quantum physics and electrical engineering. His story sounds a little like the chemistry genius Walter White from “Breaking Bad” starting up a meth lab, but without the crime.

In actuality, Snyder’s studies have limited application to the field, which can feel more like an artform than a hard science. A lot of what he knows about pedals comes from trial and error and advice from musician friends. “Some of those folks can run circles around me,” he admits.

These days, a plant has taken over much of EAE’s manufacturing. So, if there aren’t any fires to put out, Snyder spends much of his time being creative. He’ll often refer to a pedal as a “piece” as if he were working on a painting. Above his workbench, there’s a printout that reads:

The Creative Process:

- This is awesome

- This is hard

- This is s---

- I am s---

- This might be ok

- This is awesome

It’s something Snyder copied from Rick Perry, the art director for Dimension 20, a “Dungeons & Dragons” game show. If you hadn’t picked up from the weapon-related pedal names and art, Snyder loves D&D. He has played as a seafaring half-orc pirate in an ongoing campaign with his wife and friends every weekend since 2017.

Perry’s creative steps, which have a fittingly New Englander self-flagellation to them, have become a shorthand in the EAE shop. Some days, Snyder’s at a four (“I am s---”). The prototype pedal he’s working on is at a five (“This might be ok”). And the company as a whole?

“That’s at a five,” he says. “And I’m just hoping we stay there.”